Keep South Carolina Wild

July 12, 2023

SCWF Note: This is a terrific article about an amazing SC species, the threats that it faces, and legislation that could help to save it. SCWF is involved in a lawsuit to protect the ephemeral ponds on the Cainhoy peninsula mentioned in this article as “being actively destroyed…this year” – these wetlands are critical for the survival of this species, and many others. SCWF is also actively pushing for the passage of the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act mentioned in this article, and we applaud Senator Graham for being a co-sponsor!

Article by Clare Fieseler cfieseler@postandcourier.com

Published at: https://www.postandcourier.com/environment/with-growing-subdivisions-and-drought-is-it-too-late-to-recover-the-goldilocks-frog/article_aff42fc8-0627-11ee-8f13-57539b227266.html

Grace Beahm Alford gbeahm@postandcourier.com

BERKELEY COUNTY – Beyond a locked gate and an old logging road lies Sunset Pond – an ephemeral oasis known to South Carolina scientists as the last stronghold of the Carolina gopher frog.

The name “Sunset Pond” doesn’t appear on maps. In this southern stretch of the 259,000-acre Francis Marion National Forest, surprisingly close to Charleston’s growing sprawl, subdivisions and drought are already threatening the frog’s survival. No need to add passersby to the mix.

The pond’s secret location has helped it grow into a giant conservation experiment. Listening devices, orange flags, underground tubes and the scars of targeted fire management dot the landscape.

To stabilize the gopher frogs’ numbers, a husband-and-wife team of conservation specialists – working closely with state and federal scientists – have been mapping and preparing the area for the release of almost 700 captive-reared froglets back into the national forest.

The goal here is to find out if early intervention can stop the gopher frog’s population decline before the species winds up on the list of federally endangered species. Nationwide, less than 10,000 Carolina gopher frogs remain and, according to Andrew Grosse, the S.C. Department of Natural Resource’s state herpetologist, “populations in South Carolina have declined dramatically.”

On June 1, the couple – Ben Morrison and Sydney Sheedy – arrived at Sunset Pond with a federal employee who carried a cooler full of 30 food cups with lids tightly attached. Each container contained a speckled froglet, maybe the size of a wet bar of soap. Some were sage green, others were dark olive. Most had just lost their tadpole tails, and a few had vestige tails attached.

“Where do you want to start?” Morrison said, with a heavy sigh. He’d already released 500 froglets at this location over the past month and each needed to be carefully placed, by hand, next to pre-identified burrows in the ground that gopher frogs need for safety and survival.

This work is both time-consuming and a long time coming.

Seven months ago, Morrison and Sheedy had collected these same critters from the waters of Sunset Pond when they were just eggs. Once brought to the federally run Bears Bluff National Fish Hatchery on Wadmalaw Island, tadpoles later emerged and then slowly metamorphosed under the care of James Henne, the hatchery’s project leader.

The Endangered Species Act, which turned 50 this year, has been effective at preventing extinctions but quite ineffective at actually recovering species to healthy populations. Listed species get trapped at numbers that are perilously small and genetically defunct.

Carolina gopher frogs are an ideal species to keep out of this trap by getting ahead of the ball, intervening with this so-called “head start” program now while there are still a few robust breeding ponds remaining.

It’s an approach known as proactive conservation. Some think it’s the future of U.S. conservation. Others doubt whether it can overcome a warming, increasingly crowded America.

Not endangered, yet

Carolina gopher frogs are listed as endangered under S.C. state law but under federal law they are a “species at-risk.” That designation means that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is still reviewing its case for federal endangered species status.

Currently, there are over 1,300 species listed as threatened or endangered under U.S. law. But less than 60 of them have been removed for making a full recovery.

In other words, species typically land on the endangered species list when it’s too late for them to recover. Their numbers are so low when finally given protections that conservation measures become expensive and extreme. The petition process can drag on, taking three years or often longer. Between 2000 and 2009, the average wait time was 10 years.

The too-little, too-late pattern in the Endangered Species Act system was first uncovered by scientists in 1993. According to a study published by some of the same scientists last year, nothing’s really changed.

Here’s another problem: Some endangered listing or delisting decisions are swayed by political interests – instead of science, as the law requires. The Post and Courier has previously covered such instances in the cases of the dwarf-flowered heartleaf and the northern long-eared bat.

A promising new bipartisan U.S. bill called the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, or RAWA, was built to address some of the endangered species law’s shortcomings, including a heavy focus on proactive conservation.

It would invest $1.4 billion annually into proactive conservation for wildlife in decline, species that are officially listed but also many that are not, like the Carolina gopher frog. The Bears Bluff hatchery and the three other Fish and Wildlife hatcheries currently experimenting with gopher frog head-start programs, in the Carolinas and Georgia, would stand to benefit from RAWA.

A large chunk of the money from RAWA would go directly to state agencies, like the S.C. Department of Natural Resources, which often partners with conservation nonprofits. These partnerships have proven key.

Morrison and Sheedy work for the nonprofit Amphibian and Reptile Conservancy, which partners with both DNR and the federal agencies. DNR also partners with the Riverbanks Zoo and Garden to run a similar, albeit smaller, head-start program for gopher frogs in the state capital of Columbia.

The RAWA bill failed to pass the U.S. Senate last year. In 2023, wildlife advocates get another shot at pushing it through. South Carolina Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham has already signed onto the 2023 version of the bill. Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C., has not.

Even if RAWA passes at the federal level, local development could still work against the frog and its shot at recovery. In the city government offices of Charleston, which permits development for land where frog-breeding ponds still exist, the species isn’t on the radar.

‘Goldilocks’ frogs and subdivisions

“They’re kind of a Goldilocks frog,” said Morrison while releasing a froglet next to a half-filled Sunset Pond ringed with blue flag irises. “They only really like a specific type of habitat.” In simple terms, like the girl in the fairy tale they want the bed that’s just right.

Ephemeral ponds in longleaf pine habitats are about as specific as you get. The frogs depend on these ponds for breeding, which brim with rainwater only seasonally before the waters disappear, almost magically, in the summer heat.

But entire pond habitats are at risk of disappearing under a pile of bulldozed fill. Ephemeral ponds are being actively destroyed on the Cainhoy Peninsula this year.

Henne, the hatchery leader, said he reared frogs this year that were part of a “rescue effort” from a pond, located just outside the borders of the Francis Marion National Forest, that will be the future site of Point Hope townhomes.

The new 45,000-occupant development will be the size of a small city. The mixed-use development once called Cainhoy Plantation, now Point Hope, sits on 9,000 acres of currently undeveloped timber and forest land in the city of Charleston in Berkeley County. The developers received federal permits last spring from the Army Corps of Engineers to destroy nearly 200 acres of wetlands, which are protected under the Clean Water Act.

Under current interpretations of the Clean Water Act, their isolation from other waterways under the law puts them in danger of becoming subdivisions.

U.S. Supreme Court cases in recent years have called into question the Clean Water Act’s jurisdiction over so-called “isolated waters,” such as ephemeral ponds.

Under a recent Supreme Court case, those waters are still in a legal gray area over whether they are protected. Federal agencies have been slow to give guidance on how to treat these ponds, leaving developers free to move ahead in the meantime.

“This is just another example of all the harm of this proposed Cainhoy development. It could destroy imperiled species in the South Carolina Lowcounty,” said Chris DeScherer, an attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center.

And because the frog is not listed as endangered, its habitat – mainly the ponds and connected forest patches around them – don’t receive protections under the Endangered Species Act. The city of Charleston says it’s not accountable for either.

“Environmental and wildlife issues are outside the purview of the city’s site-review process. Those matters are handled by subject-area experts at the appropriate federal and state agencies prior to the issuance of relevant city permits,” said a spokesman for the city of Charleston, which in 2014, approved the rezoning of the Cainhoy Peninsula, enabling up to 18,000 homes to be built there.

Because ephemeral ponds are not fed by creeks or streams, they usually dry up in the heat of summer and don’t support the fish that might otherwise eat the frog eggs and tadpoles. Without fish, ephemeral ponds are perfect gopher frog nurseries.

Ponds that remain full year-round, like the ones created for townhome developments and golf courses, actually displace gopher frogs – they don’t support them.

Henne reared the eggs rescued from Cainhoy Peninsula bulldozers on Wadmalaw Island. Once they metamorphosed, Grosse and other biologists from DNR released them in an undisclosed ephemeral pond on protected land.

“Due to the sensitive nature of this state endangered species, we have made an effort not to disclose sensitive location information of our release site,” Grosse said.

But, wherever it is, the frogs’ new pond home is not safe from the extreme droughts in South Carolina’s future.

Drought and doom

“Because of development, there are fewer ponds,” said Brian Crawford, a herpetologist who assessed the future viability of gopher frog populations for his postdoctoral work. “But the other big problem is climate change.”

Of the 10,000 Carolina gopher frogs that remain, all of them are within the rapidly warming and drought-stricken Southeast region. But, as Crawford and his colleagues concluded in a 2022 publication, the future intensity and frequency of droughts is still uncertain.

If the next 30 years looked like the last 30 years, with about four years of drought per decade, then there is good news for gopher frogs: They have an 89 percent chance of avoiding extinction.

If things get drier, as government agencies predict, things look more bleak. Under a future of more frequent droughts, the likelihood that the species survives drops to 70 percent across their Southeastern range. That also increases the likelihood of local extinction in certain states. In other words, the gopher frog could disappear completely from states like North and South Carolina.

Notably, Crawford’s model projections only considered future drought and didn’t factor in whether future development might further push these numbers towards extinction.

Crawford, now a scientist at the consultancy firm Compass Resource Management, said that drought is already affecting the quality of ponds as breeding ground. Instead of yearly breeding, he’s seen more sparse breeding over time, perhaps as some ponds fail to fill up in the winter or dry up too quickly in the spring.

Sheedy, the conservation specialist, said she’s seen this phenomena, too, confirming “There is one pond that we found recently that historically supported gopher frogs, but that pond is just barely hanging in there. It has egg masses but they aren’t doing great.”

For now, Francis Marion National Forest still has at least three populations, or clusters, of gopher frogs that still breed almost yearly across seven ephemeral ponds. Not being able to control the climate nor encroaching development, scientists are focusing their efforts here.

If successful, this year’s release of 700 frogs would be almost triple the number of frogs as 2019, when the “head-start” program started, as an experiment, by scientists who didn’t want to wait.

Published at: https://www.postandcourier.com/environment/with-growing-subdivisions-and-drought-is-it-too-late-to-recover-the-goldilocks-frog/article_aff42fc8-0627-11ee-8f13-57539b227266.html

Tags: Cainhoy Plantation, conservation, Frogs, Habitat, Post & Courier, RAWA, SCDNR, SELC, USFWS, Wetlands

SCWF had a wonderful event at Harbor Island on April 29 & 30, 2018 to observe and learn about Horseshoe Crabs & their spawning cycles, and the shorebirds that depend...

St. Joseph Catholic School in Columbia created a Schoolyard Habitat in 2022, and it is still thriving! Nectar plants attract butterflies and other pollinators, and milkweed provides critical habitat for...

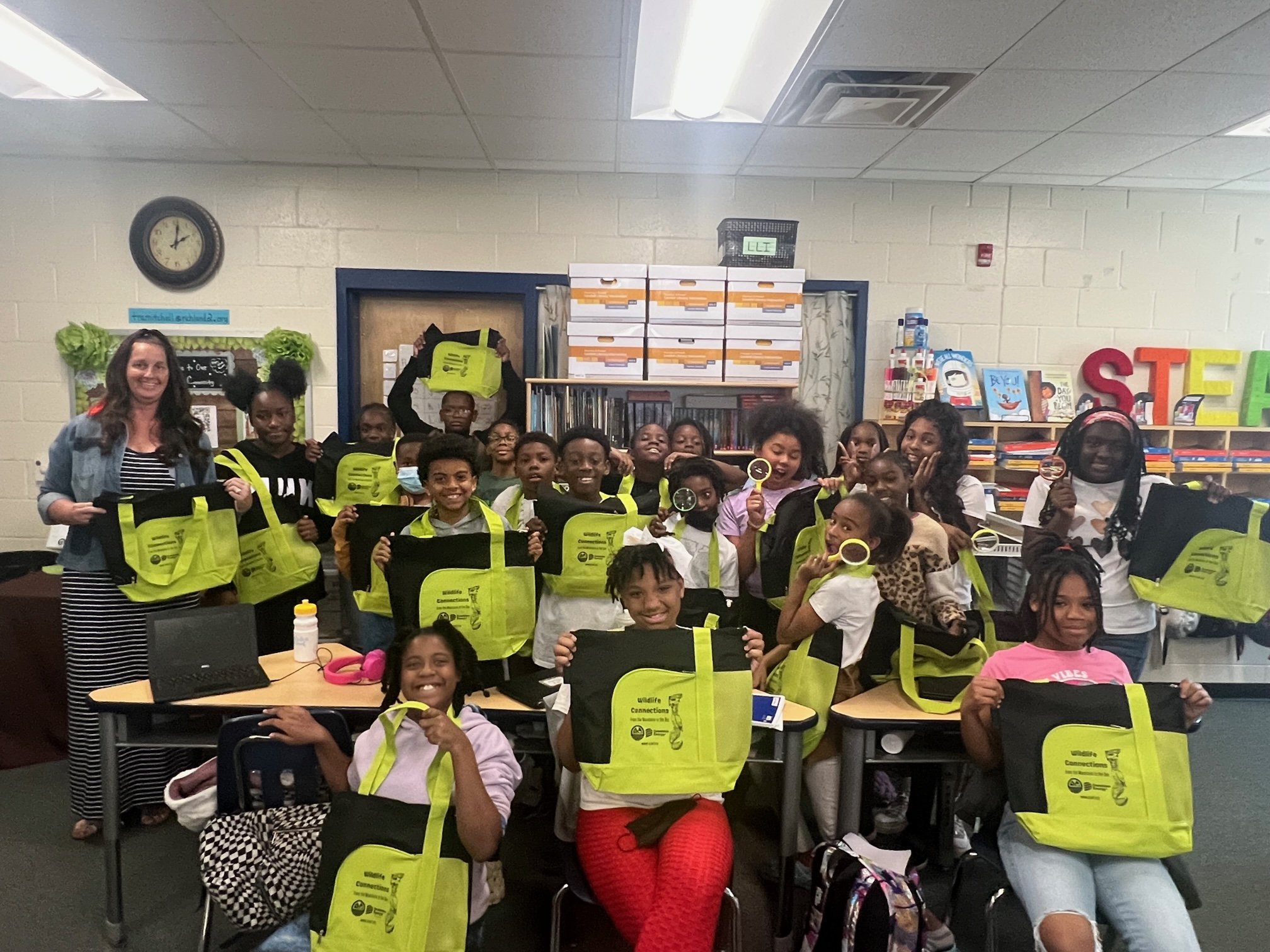

The first year of “Wildlife Connections from the Mountains to the Sea” program was a success! This unique science-based curriculum, developed by SCWF staff, teaches students how wildlife is intricately...